The Long Game

Beat the odds: Plenty of myths about your brain are passed around (and accepted). This month, you’ll discover one of the biggest and most relevant myths you’ve ever heard. And, as important, it can change your life. Ready for a big “wow”?

BACKSTORY

We notice some biological changes within us; others are invisible to the naked eye. Let’s begin with the building blocks of our body: genes. By 2003, the 2.7-billion-dollar Human Genome Project (HGP) had completed two streams of research, one public and one private. Their ambitious research goal was to uncover the biggest secrets of human genes. Initially, organizers thought human complexity would mean we have more genes. Maybe humans have 80,000 and 140,000 genes, some thought. That was dogma number one. However, multiple long-standing dogmas in biology were turned upside down.

When HGP scientists discovered that humans have about 22,000 genes, jaws dropped worldwide. Now you know that humans have the same number of genes as a sea sponge (Steffen et al., 2023). Water fleas have more genes than humans; they have 31,000 genes! (Colbourne et al., 2011). What’s the relevance of this? Read the following line carefully. How on earth could humans survive and thrive with such complexity and do it with so few coding instructions from our genes?

DNA does indeed carry immutable messages for characteristics such as hair color, susceptibility to disease, eye color, skin color, and facial or body characteristics. Given that some DNA cannot be modified, the remaining DNA must have a survival benefit. The apparent “lack of modifiable genes” suggests that there must be other mechanisms by which humans can survive and thrive.

Humans live year-round in all types of climates, have all types of social relationships, do all types of jobs, and have varied customs, laws, political structures, religions, educational systems, population sizes, and on and on. This puzzle seems to be about understanding our genome, but it turns out to be more than that. There is more to it all.

As one of the lead researchers in the HGP, renowned genetic biologist Dr. Craig Venter has spoken at many conferences since the project was completed. Venter revealed, “Human biology is far more complicated than we imagine. Everybody talks about the genes that they received from their mother and father for this trait or that. But, in reality, those genes have very little impact on life outcomes.

“Genes are absolutely not our fate. They can give us useful information about the increased risk of a disease, but in most cases, they will not determine the actual cause of the disease. Most biology will come from the complex interaction of all the proteins and cells working with environmental factors, not driven directly by the genetic code.” (pg. 2 Anand, et al., 2008).

Did you catch that? Your biology is NOT driven by your genetic code (DNA). That was dogma number two.

However, when used well, your body’s science can help you accelerate thriving. If you are still on board and want to move from survival to thriving, the next brain bytes may give you some answers.

It used to be either genes or environment. But it’s no longer environment or genes. Venter’s comments, coming from one who understands the human genome better than most, sent shockwaves through the biology community. What if the environment, instead of working alone, influences our genes?

This is a critical new paradigm. It reveals that environmental influences, along with our ongoing perceptions of the environment, control much of our genetic activity. Can you learn how to thrive by getting your genes to help? Yes, that is exactly what the science is telling us.

Typically, science stays stuck with a belief system (dogma) until it is overturned. There are dozens of these… the earth was flat until it wasn’t. Earth was believed to be the center of the solar system until it wasn’t. We used to believe it was either environment or genes that ran our lives… until we learned that, too, might be dogma. Science is a never-ending process of discovery. What usually follows is the process of skepticism, new experiments, studies, and trials. Scientists are skeptical by nature.

We know DNA is an influencer, but what if it is no longer at the top of the life scheme for all changes? What if the environment plays an equal or even greater role?

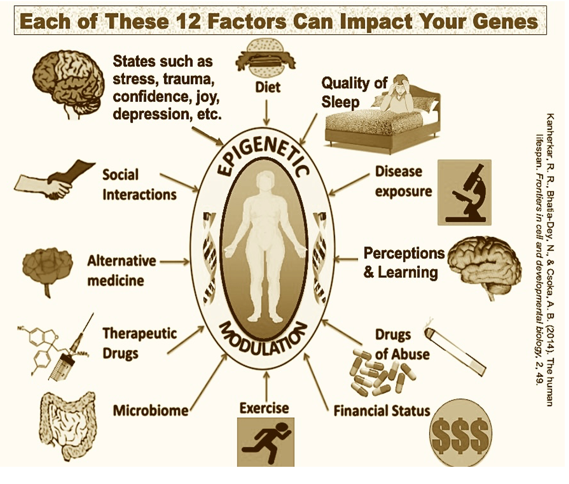

There are dozens of ways environmental influences can impact our genes; we call it epigenetic modulation. Examples include genes that are suppressed, activated, damaged, or modified. Plus, there are real-world environmental influences that can become autonomous and life-changing throughout our lives. But how? Epigenetics is the interaction between our genes and our environment. Experimental science shows that even cultural conditions can lead to measurable differences in the specific cues that trigger core brain structures. (Campbell & Garcia, 2009).

The DNA dogma model inferring genetic control translates to “controlled by genes.” But we are not “controlled” by our genes. We don’t have sufficient genes to provide the thoughts and actions for every bit of complexity in our lives on a planet with eight billion other unique human lives. The human epigenome (your 22,000 genes) is very mutable; it changes during child development but also in many ways as we grow older and get exposed to external environmental cues (Grunau, Le Luyer, Laporte & Joly, 2019). What are the types of cues that influence genes?

Practical Applications

Here is one tool to start the rest of your life. There are at least a dozen simple ways you can influence your own genes. Check out the graphic below and determine where you can start. In the upper left corner (the 11 o’clock position if it was a face clock) is a topic called states.

Your physiological state (stressful, joyful, fearful, excited, welcoming, etc.) constantly generates chemical messages that are sensed by your cell membranes. These messages then send a signal to DNA in the nucleus of every cell. That signal then informs RNA, which sequences proteins, and the action begins. Why is this relevant?

Your physiological state (stressful, joyful, fearful, excited, welcoming, etc.) constantly generates chemical messages that are sensed by your cell membranes. These messages then send a signal to DNA in the nucleus of every cell. That signal then informs RNA, which sequences proteins, and the action begins. Why is this relevant?

We had a complete misperception of the nature and role of DNA in controlling our lives. In some ways, the DNA in our cells is comparable to the hardware of a computer, and the epigenome is the software that instructs the genes when, where, and how to work. Think of your cell as functioning like a programmable computer (Jirtle, 2022). When the biochemistry of your emotional states (stressed, calm, excited, relaxed, fearful, joyful, etc.) reaches the cell membranes (you have over 30 trillion cells for landing spots), the cell membrane senses if you are in danger or safely having fun. If you are in danger, the cell membranes sense the body’s biochemistry and signal to your DNA, “Focus on Survival, Freeze alternative choices” (i.e. don’t think about lunch or a shopping list). Your body then sends extra blood to your lower limbs if you need to escape. It’s all about flight, fight, or freeze. Or, if your state is loving, kind, and joyful, the body produces different chemicals, such as serotonin or oxytocin. These messages tell your body it is safe to charge ahead, grow, and flourish (Gustafson & Lipton, 2017).

It is your perception of reality that generates your emotions. Those emotions change your body’s chemistry. The change in blood, enzymes, and hormones communicate to the outer part of the cell membranes to signal the DNA in each cell’s nucleus. Notice the dance. Environment impacts DNA just as much as DNA impacts the environment. Loving, kind, and joyful people are constantly sending positive signaling to their DNA. As a result, life is better for those who are being positive. You may have more to do with how you will eventually turn out than you may have thought.

Personal: We all need a reason to believe better things are possible and on the way. The second you lose hope, your body slumps, and “I quit” messages are sent to your cells. “My dream is over; I might as well walk away.” Those are fiercely damaging signals to send to your own body.

From reading the above, you already know that the signals you send to your cells are a critical part of the process of thriving. Of course, what you do want is the capacity and motivation to thrive. The opposite of hope is doubt, despair, and, at times, giving up. When those feelings emerge, create your own cue or trigger to get back on track. Here’s how to do that with three simple tools.

Foster Hope with Openings. Use phrases like these in a conversation: “This seems doable.” “Let’s take a different path.” “Maybe someone else has figured this out.” “What’s worked before (or is working now)?” or “Maybe there’s another way.” These hope signals are critical for learning the process of thriving; they are more than motivation, they are substance (Murphy, et al., 2024). Hopeful is different than Pollyanna.

Foster Hope with Complaint Deletion. Stop the continuous stream of complaints. Before I knew better, I complained almost constantly. I pointed fingers and denied all blame. Complaining about constant changes implies the situation is out of your control and increases stress levels. It also tells your cells to send messages to the cellular DNA that you are a quitter, not a go-getter. The message is, “Things are bad. There’s no hope. It’s all out of my control…” That targeted message influences your DNA, and poof! You’ve done it again. That’s what survivors do to survive.

Start with Something Simple. I began by going for 5 minutes without complaining. Then, I was able to get to thirty minutes. Today, I go an entire week without complaining. I stopped there. I was happy about my growth and don’t mind a rare day to vent. Today, I live with my “margin of joy” with one complaint per week. Embrace what you have, sharing gratitude daily. Bringing joy is what it means to relish every day and promise yourself to make your day (and others) thoroughly amazing. If you start seeing changes, send me a quick email to eric@jensenlearning.com.

Closing Time. Now, for my biggest fear: Maybe you still use the ‘time bias.’ Many will read this newsletter and then respond, “I’m just too busy; I’ve got no time for those changes to begin thriving.” If you feel that way, I am sorry; I have failed you. I failed to activate your choice of playing the ‘long game.’ Biases are shortcuts to save time and are often about the ‘short game.’

You see, life goes by so fast that many would say, “Live in the moment, smell the roses; life is short.” And they’re right. Life is about savoring the smell of the flowers, eating a great meal, and enjoying hugs from friends and family.

But most everything worth having over a lifetime also requires the ‘long game.’ At school, this includes building relationships and fostering cognitive capacity. At home, it includes maintaining relationships, appreciating the daily blessings, and saving for retirement. Choose right now; what have you decided on—long or short? Then begin, right now.

Eric Jensen

CEO, Jensen Learning

Brain-Based Education